Traditional blankets from the ethnological collections

Various types of patterned blankets are the most spectacular textiles in traditional interior decoration and a significant kind of folk art. In the prosperous regions of Western Finland, many types of blankets were woven, especially from the late 18th century onwards, as the general standard of living rose. In particular, the number of textiles increased in farmers’ homes in South Ostrobothnia and Satakunta in the 19th century.

Blankets in Eastern Finland were significantly more modest in terms of both technique and appearance than those woven in Western Finland. In the Savo-Karelian region, people still lived in dimly lit, chimneyless cabins, so not that much time was devoted to knitting home textiles. Ordinary ribbed blankets were enough there. However, threaded blankets, weft-patterned raanu rugs and täkänä double cloths were also made in the late 19th century in Western Savo. In the region of Eastern Finland, the exception was Kymenlaakso, the south-eastern area rich in handicraft tradition, where various patterned blankets were already being woven in the 19th century.

In this researcher’s choice, I present blankets made with four different techniques: threaded blankets, embroidered blankets, täkänä double cloths and silmikkoraanu grid rugs. For the above reason, the blankets I have selected are mostly from Western Finland.

Threaded blanket (pujotuspeitto or kuvatäkki)

The threaded blanket is a woven textile based on a weft rib, plain weave or, occasionally, rosepath, in which the patterns are made by threading the pattern wefts between the main wefts. The threading is done either with fingers or with a special shuttle.

Finland’s oldest threaded blankets from Häme date from the 18th century, and their colours and patterns refer to Sweden. Häme’s oldest threaded blankets have similarities with the ryijy rug art from the same area. These more modest and affordable blankets often replaced ryijy rugs, borrowing their colouring and pattern motifs: octagram, heart, tree and flower themes. The patterns of the blankets are usually symmetrical and geometric. Other features adopted from ryijy rugs include the highlighting of the edge, cross-stripes and the prevalence of dark base colours.

Threaded blankets were produced in Häme, but also in Satakunta, South Ostrobothnia and Southwestern Savo, and on the shore of the Gulf of Finland between the Kymijoki River and Vyborg. Each area had its own threading and patterning technique.

The most commonly known threaded blankets are from Häme and Satakunta, featuring relatively large flower motifs or geometric patterns (octagram, heart, hourglass, diamond) on a dark background. Tightly woven blankets from Southeastern Häme used lighter colours and soumak weaving, which differed from blankets from other parts of Häme.

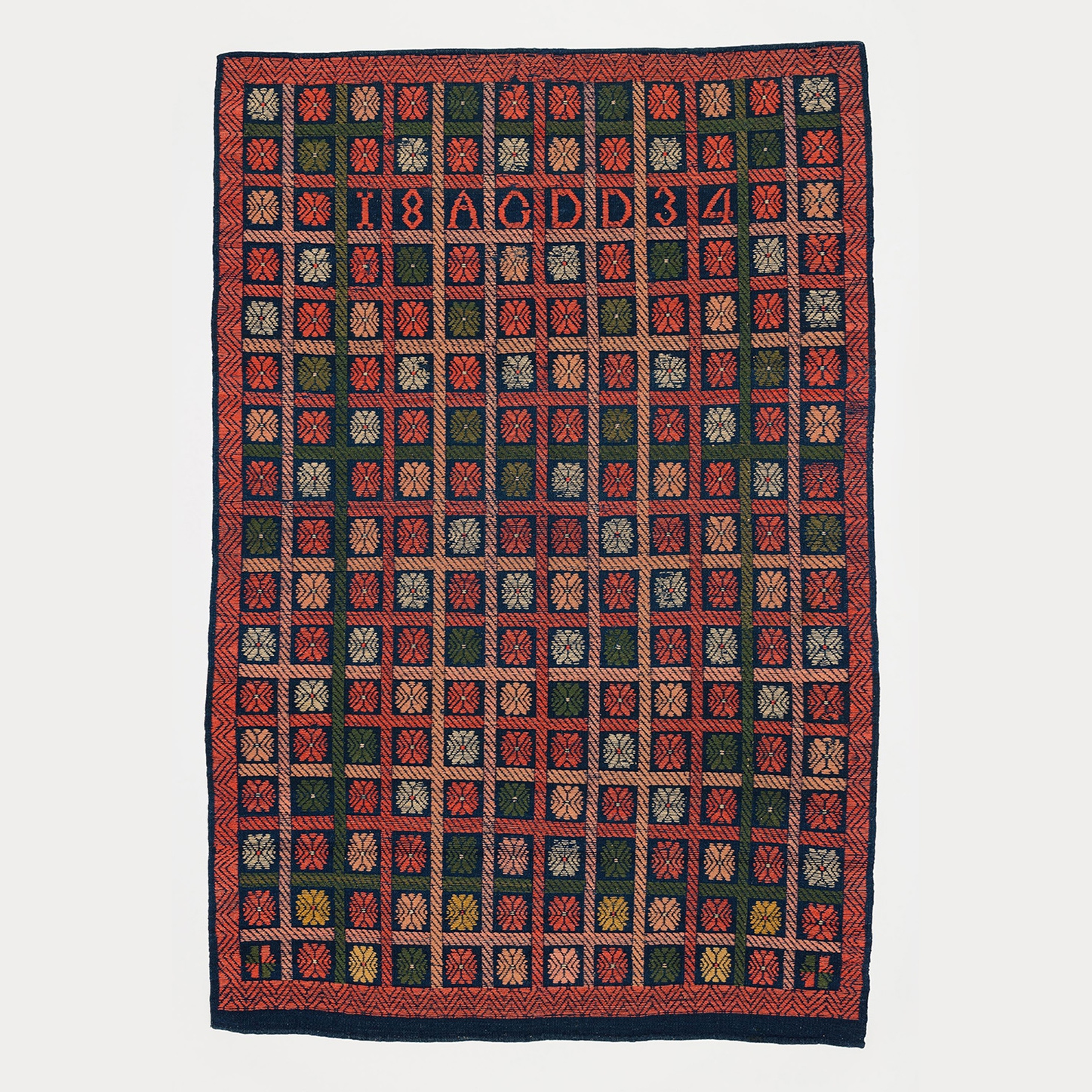

In late 19th century, “plättiroiti” blankets were woven in the eastern parts of South Ostrobothnia, featuring patterns consisting of small squares, usually with single-colour and floral motifs.

Kymenlaakso’s graceful threaded blankets are characterised by cross-stripes and the dominance of red. Around Iitti, Jaala, Valkeala and Heinola, the blankets were threaded using stem stitch.

Threaded blankets were used in beds and sleighs, older blankets for horses. Threaded blankets were woven by professionals as well as dexterous wives and daughters. They were also made as dowry gifts.

Photos: Ilari Järvinen, 2021

Select an image for more information

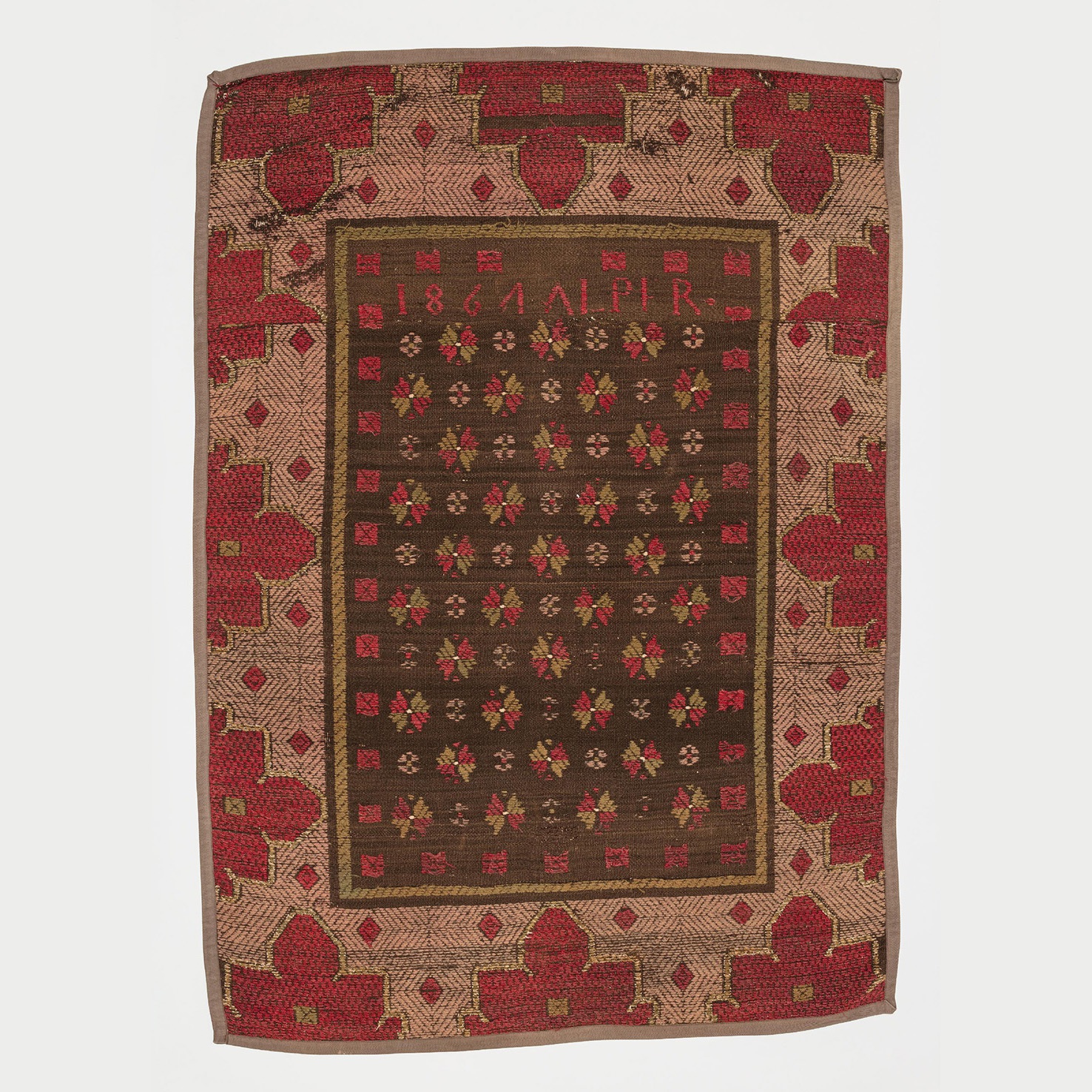

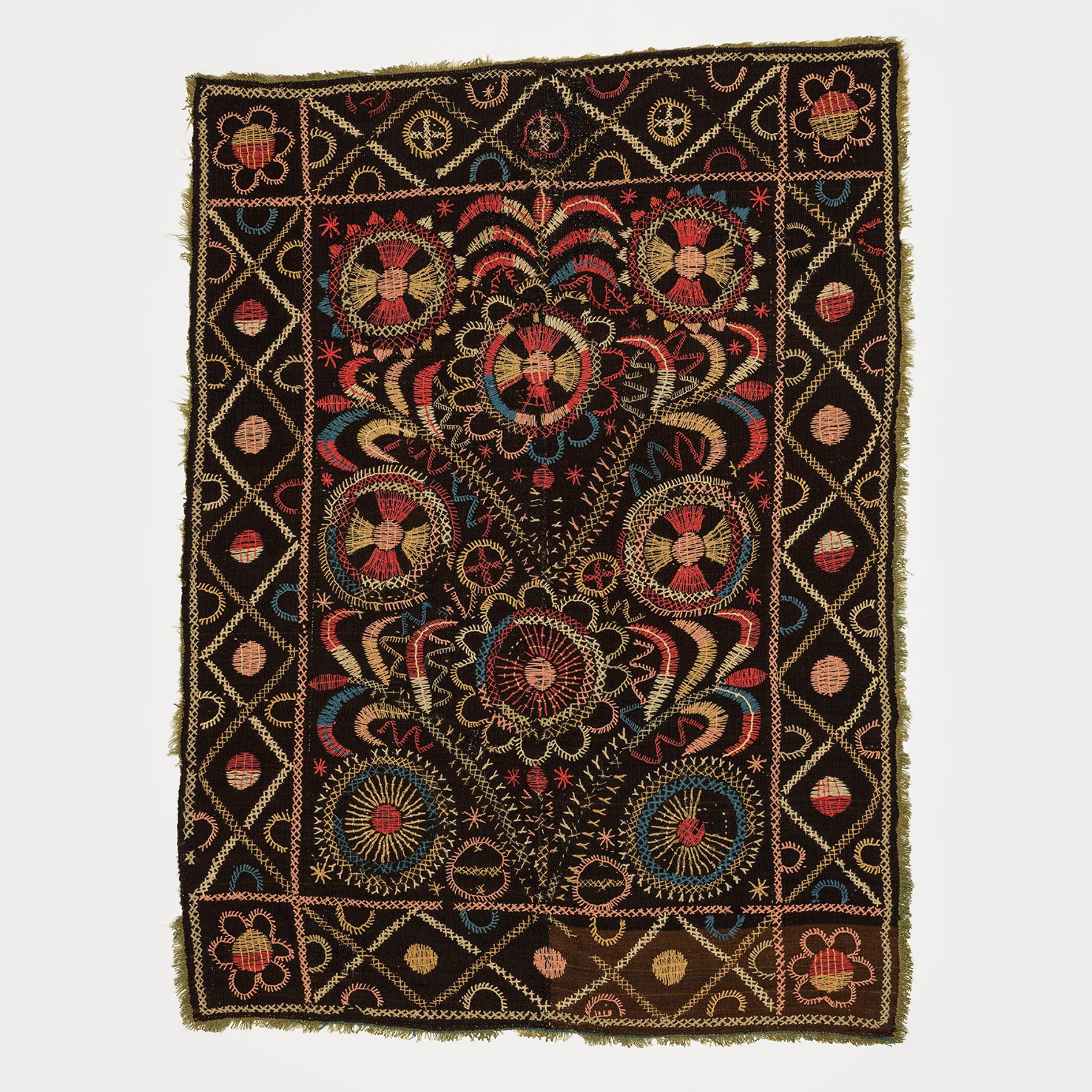

Embroidered blanket

The embroidered blanket is a lightweight blanket resembling a raanu rug, with patterns sewn on the surface using wool yarn of different colours. The fabric of embroidered blankets is usually home-woven rib with a linen warp and natural black wool weft. The ribbed fabric is easy to make, since it has a simple structure. The craftsmanship of embroidered blankets is based on the embroidery, which was made with various stitches with a large darning needle while the fabric was stretched into a frame.

Various geometric patterns were used as decorative motifs in the embroidery of the blankets, often flower motifs adapted around a wreath. Popular symbols included a flower and a crown, and the blankets were often marked with the year of completion and the owner’s initials. The composition of our foremothers’ blankets is rich. The patterns are plentiful and sprawling. According to Grönlund and Lehto: “The patterns are sometimes so frequent that the creator seems to have had some kind of fear of empty spaces. The work was not too precise, but joyful. No compasses or rulers were used to shackle creativity, not always even a tape measure. The lighting may also have been inadequate.”

The composition, motifs and colouring of embroidered blankets show the influence of cultural styles, which can probably be explained as a phenomenon parallel to the stylistic development process of ryijy rugs. The black base of the blankets suggests the Gustavian style, so the origins of these blankets are in the late 18th century. Embroidered blankets can be dated exceptionally accurately as an expression of folk art.

The embroidery of blankets began in Finland in the late 18th century. The first embroidered blankets were probably brought to Finland by carpenters who had worked for many years at the Karlskrona warship building yard in Sweden. This should explain the relatively small area in which the blankets were distributed. And the fact that the way in which they were embroidered was probably adopted in Sweden.

The aforementioned small distribution area in Finland covers two central areas: the Swedish-speaking coast parishes of Ostrobothnia and Northern Satakunta. The former radiated its influence to its Finnish-speaking vicinity, the latter to Central Finland and Häme. These regions, in turn, extended their influence a little further to the south and east. Individual blankets have been found in, for example, Sääksmäki, Lempäälä, Karstula and Kuhmoinen.

Embroidered blankets were in fashion from the 1820s to the 1840s in Ostrobothnia, but they were still being made in Satakunta and Central Finland in the 1860s. At the same time, the heyday of the popular ryijy rug also came to an end.

Embroidered blankets were used in sleighs, in beds and as palls for the deceased. They could also be hung on walls for decoration at parties. In addition, thinner blankets were used as curtains for bunk beds and as tablecloths.

Embroidered blankets were valuable property, desired family heirlooms and dowry gifts. They were also recorded in estate inventories. The most skilfully made blankets were created by professionals.

Photos: Ilari Järvinen, 2021

Select an image for more information

Threaded blankets collected by artist Germund Paaer from Satakunta with the main number K7036

In 1905, ten threaded blankets collected by the artist Germund Paaer (1881–1950) from Satakunta were purchased for the Antell collections. Paaer’s first wife, Sigrid Wickström-Paaer (1885–1923), was a textile artist, and they had a villa in Kihniö, on the Iso-Liettinen island in Lake Kankarijärvi, where they spent their summers. Below are four of these blankets with the main number K7036:

Select an image for more information

Täkänä double cloth

Täkänä double cloths feature two layers, meaning that they consist of an upper and lower fabric that switch places at the position of the figure. In other parts, the fabrics are separate, which forms cavities in the cloth. Every weft of the double cloth is picked separately with a stick, which means that the weaver can devise figures rather freely. The pattern is drawn on squared paper and matched to the yarn count of the warp. The pattern is adhered to by counting the yarns. Double cloths normally use a form of single weave, the most common of which is plain weave. Different weaves can also be used in the upper and lower fabric.

Täkänä double cloths are among our oldest traditional textiles. In the Finnish region, double cloths have been made since the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. They were woven in monasteries for ritual purposes and in upper-class homes, castles and manors to serve as utility and export items. The oldest surviving double cloth in Finland is the altar frontal of the Marttila Church (H2362:5), which is part of the National Museum of Finland’s collection and has been dated back to the Middle Ages.

In the 17th century, mentions of Finnish double cloths start becoming scarcer and vanish entirely in the 18th century. At the same time, however, double cloths were being made across the rest of Europe and the Nordic countries without interruption.

In Finland, the weaving of double cloths re-emerged in 19th-century Southern Ostrobothnia, where the craft gained a strong foothold thanks to the skill and large number of professional weavers. The new weaving text books published early in the century also contributed to the increase in popularity. Moreover, double cloths rose to a prominent position partially due to the fact that weaving wall cloths and rugs was not very common in Ostrobothnia. Another exception was the Swedish-speaking area where, according to Hjördis Dahl, double cloths were almost completely absent.

Double cloths were used as bed covers, tablecloths and, at the end of the 19th century, wall cloths. In terms of their colour schemes, the common double cloths were red and white, blue and brown, black and green and, at the end of the 19th century, usually red and black. In the late 19th century, weaving schools spread the skill of weaving double cloths to the rest of Finland all the way to Karelia.

Traditional double cloths used among the common folk were usually made of wool yarn coloured with natural dyes. The schemes were mostly made up of two colours: white or black was often married with a brighter, more clearly visible colour.

In the 19th century, double cloths were large covers consisting of two pieces joined together with a middle seam. Joining the two pieces together required the weave to be extremely precise. The designs of double cloths changed fast: In the early 19th century, geometric motifs, such as stylised crosses, stars and intermeshed lines, were popular in double cloths. In the mid-19th century, double cloths were modelled after designs borrowed from twill diapers and damasks. Neo-romanticism later in the same century made plant-related patterns commonplace: grapevine, rose and leaf motifs.

Setting up a double cloth on a loom and picking patterns from the two layers of fabric takes time, precision and skill. That is why the oldest double cloth weavers are believed to have been professional weavers. Weavers mainly learned the skill through work and by observing older experts.

Select an image for more information

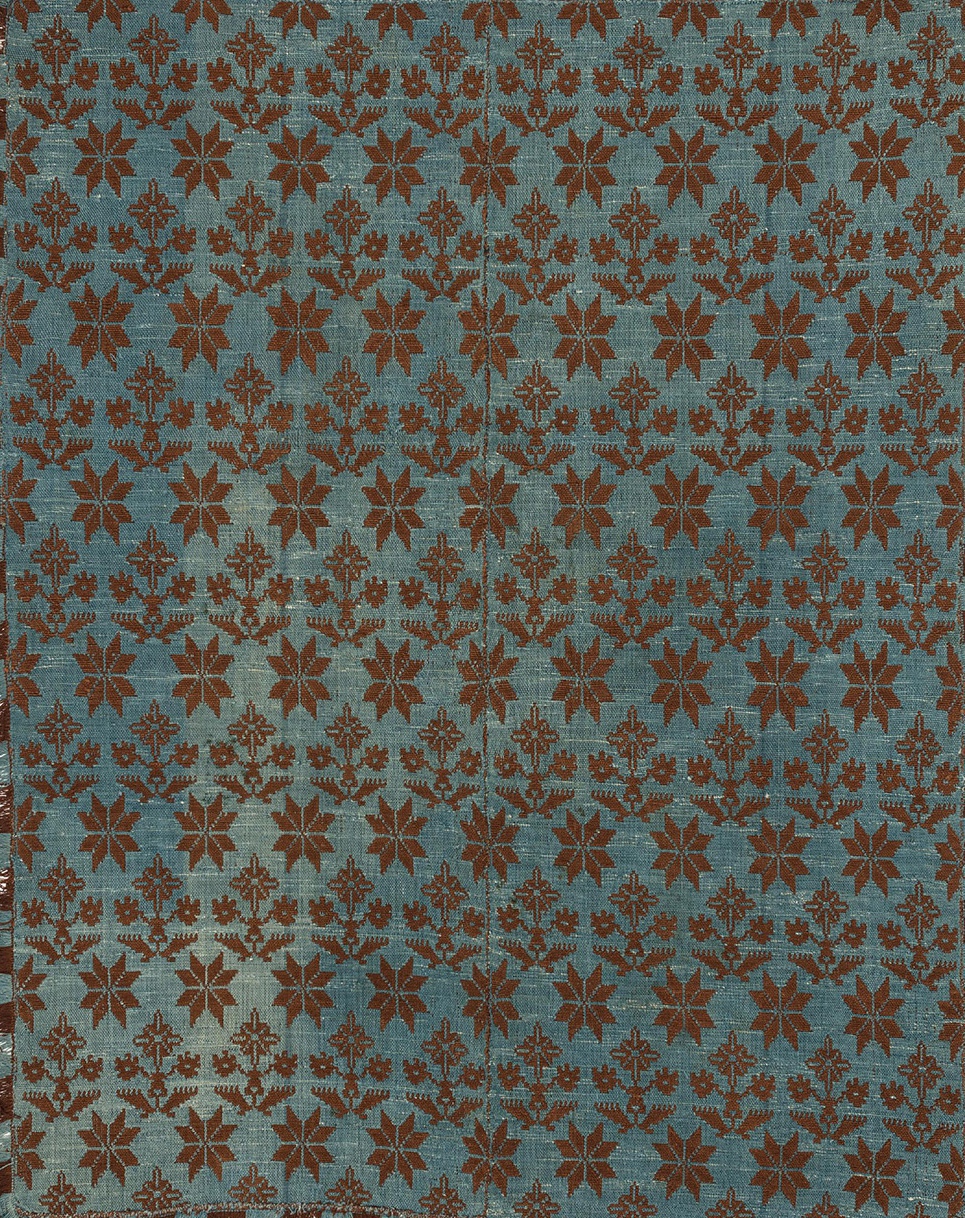

Silmikkoraanu grid rug

The silmikkoraanu grid rug belongs to weft-patterned raanu rugs. These grid rugs have a plain weave base with mesh-like diamond shapes formed by the wefts. The warps and wefts are linen or cotton. The surface of the raanu rug is often enlivened with various stripes or by threading geometric patterns of different colours following the pattern of the base: crosses, stars, hourglasses, octagrams, twigs and zigzag stripes. The patterns of the oldest raanu rugs, which were woven with shaft looms, were produced quite laboriously with picking sticks, while the patterns of newer rugs were made with the help of the additional shafts of countermarch looms.

The equivalent of Finnish weft-patterned raanu rugs, the southern Swedish västgötatäcke, has been known since the 17th century. In Sweden, this woven textile was spread by textile pedlars. In the 17th century, the weft-patterned raanu rug spread to Finland via a commercial route, for example, by peasant sailors and possibly also by professional weavers.

Central Ostrobothnia, South Ostrobothnia and Vakka-Suomi were the old core areas of traditional raanu rugs. After the 1870s, the area expanded with weavers graduating from handicraft schools, and the eastern border of the weaving area went from the Kymijoki River via Asikkala and Maaninka to Säräisniemi.

Raanu rugs were used as blankets, bedspreads, tablecloths, sleigh blankets and, in Ostrobothnia, as curtains for bunk beds.

The colours of the oldest weft-patterned raanu rugs usually came from nature, with various hues of yellow, brown, green and natural black as the main colours. In the second half of the 19th century, red and green were adopted as the most common combination of factory-made colours.

Photos: Ilari Järvinen, 2021

Select an image for more information

Sources:

Dahl Hjördis 1987. Högsäng och klädbod. Ur svenskbygdernas textilhistoria. Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland nr 544. Folklivsstudier XVIII. Folkkultursarkivet. Helsingfors.

Grönlund Irma, Lehto Marja-Leena 1985. Perinteinen peittokirjonta. Otava. Keuruu.

Kajander Marja-Leena, Kesälä-Lundahl Kirsti, Lausala Talvikki 1983. Kansanomaisia peitteitä. Kotiteollisuuden keskusliitto ry. Kauppakirjapaino Oy.

Pylkkänen Riitta 1974. The Use and Tradition of Mediaeval Rugs and Coverlets in Finland. Finnish Antiquarian Society. Helsinki.

Silpala Elsa 1995. Kantahämäläiset vuodetekstiilit. Häme University of Applied Sciences. Publication B:3. Hämeenlinna.

Spoof Sanna Kaisa 2003. Tiltun kapiot. Iittiläinen käsityöperinne. Finnish Literature Society. Jyväskylä.

Suomen kansankulttuurin kartasto. Aineellinen kulttuuri. Ed. Vuorela Toivo. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 325. Helsinki 1976.

Taisto Helvi 1979. Kirjottuja peittoja ennen ja nyt. Keski-Pohjanmaan kirjapaino Oy. Kokkola.

Taisto Helvi 1989. Rekipeitot. Ed. Anneli Bauters. Anson Oy.

Vahter Tyyni, Karttunen Laila 1952. Kirjottuja peittoja. SKS. Helsinki.

Vuorela Toivo 1973. Suomalainen kansankulttuuri.

Vuorela Toivo, Kansanperinteen sanakirja, WSOY, Porvoo 1981.