X-ray examination of medieval sculptures

X-rays show the materials, structure and methods of making sculptures. Just as in the X-ray imaging of the human body, some of the materials in the sculptures are more radiolucent, i.e. permeable to radiation, while others absorb the radiation. Radiolucent areas appear dark, while the absorbing areas are light. What makes the interpretation of X-ray images challenging is that all the different layers of the sculpture appear in the image at the same time, partly overlapping. In addition to the images, the sculpture itself is always examined in order to determine its overall structure.

The areas that stand out as the lightest are metals, most commonly nails used for securing parts of sculptures. Painted areas on the surface of sculptures can also often be discerned in X-rays, as many of the paint pigments that were popular in the Middle Ages contained metals. Gold plating, silver plating and other surface metal treatments also stand out. The wood species used and the thickness of the wood in turn influence how the wood material of the sculptures appears in the images. The different parts of the sculpture and their joints, possible locations and variations in wood species can usually nevertheless be detected from an X-ray.

Text and X-rays: Henni Reijonen, Research Conservator, National Museum of Finland.

Select an image for more information

Anonymous saint from Nousiainen Church

Madonna of Korppoo

Saint Lawrence

Mary and the Child

Archangel Michael

Saint Birgitta

Eric the Holy

Saint Margaret

Job

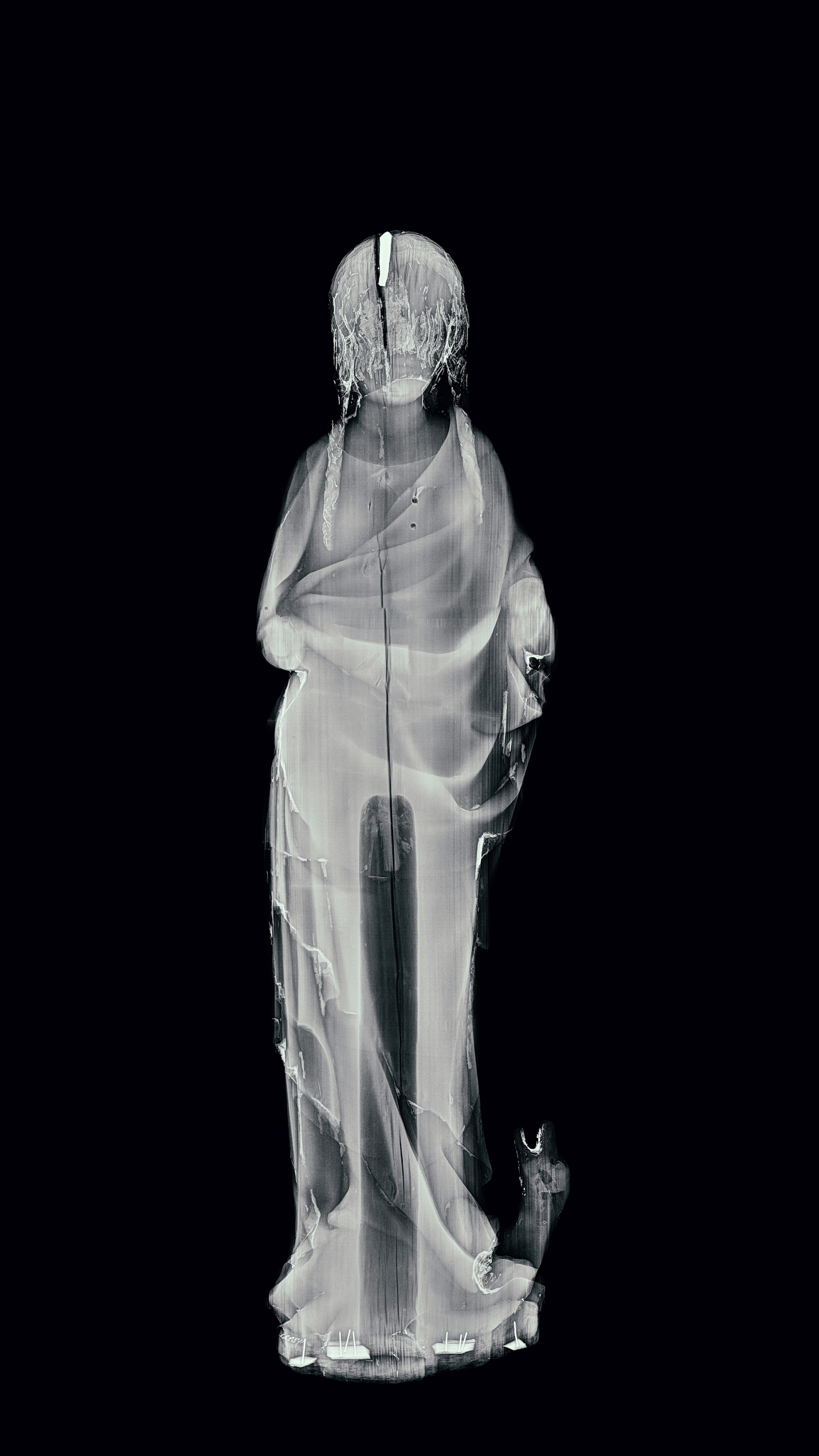

Anonymous saint from Nousiainen Church

The light lump in the head of this statue is metal, which have been revealed to be lead from more detailed examinations. The metal is in a cavity in the head of the statue. Many medieval statues have such a hollow space accessed through a hole at the top of the head. The hole was needed when making the statue: the sculptor fixed the wooden workpiece horizontally to a sort of vice, with one fastening point in the hole in the head and the other on the bottom of the statue. Later, the hole in the head was often sealed with a wooden pin, like in this case. The pin is so tight that it cannot be removed without damaging the statue.

Although the piece of metal has been imaged from different directions, it does not seem to have any recognisable shape. It looks as if the molten metal was allowed to solidify by itself, maybe as some kind of seal. Faint shapes can also be discerned under the metal. This material has not been clarified even after more detailed examinations. Sometimes, for example, sawdust accumulated at the bottom of the hole can produce similar shapes. However, it is possible that the lump of lead hides a relic.

Digital collection

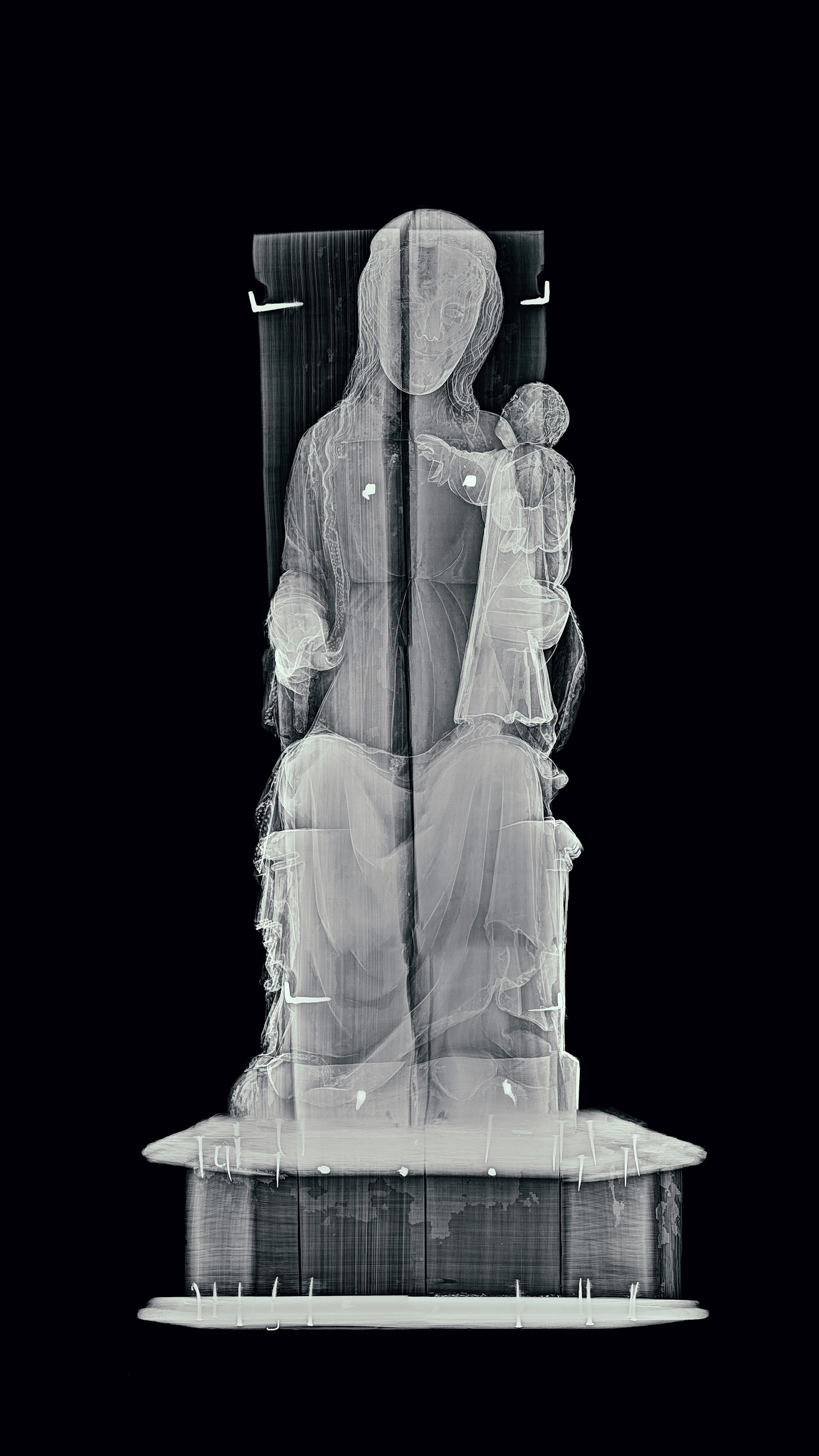

Madonna of Korppoo

This statue, known as the Madonna of Korppoo, has a very similar sister statue in Sweden. The other statue, the Viklau Madonna, had a relic inside Mary’s head, and so the X-ray imaging of the Korppoo statue was also of special interest. The cavity inside Mary’s head and the long pin that blocks it are easily discernible in the X-ray, but the small space under the pin seems to be empty.

However, the remains of paint and gold plating surfaces can be discerned in the X-ray image of the statue. Like most medieval statues, all the saints in the exhibition were originally painted. There were also several priming layers under the paint, which were used to smoothen the wooden surface and create more precise shapes and decorative motifs. In the Korppoo statue, the surface treatment has been preserved best in the area of the face, hair and chest (the paint surface of the face is also visible at the head cavity, which may make it more difficult to detect). There are empty holes in Mary’s forearms and lap, where her lost hands and child used to be attached with wooden pins. The separate crown on her head has not been preserved either.

Digital collection

Saint Lawrence

Two strange formations stand out from the hem of Lawrence’s cloak. A side image from the same area highlights the bag-like shape. The shapes stand out from the hollowed inside of the statue, which is covered by a backboard. In addition, there is a pile of some kind of dust at the bottom of the hollow space that stands out darker. What can this be?

The formations do not appear to be man-made. The statue is very “littering”: every time it is moved, some sort of lint comes out from between the backboard and the statue. Could some sort of animal have built a nest inside the statue that would have mummified into the bags shown in the image? Sculptures often contain traces of wood pests, most typically holes dug by furniture beetle larvae. However, this case seems to be different, and the process is no longer active.

Also note the exceptionally impressive forged nails used to combine the different parts of the statue. The light area at the face is also a nail struck from behind. The wood used for the sculpture was exceptionally knotty – a dominant knot is in such an important place as the face. This is a good indication of the great significance of the priming and paint layers in the final appearance of sculptures.

Digital collection

Mary and the Child

This statue has a well-preserved paint surface, which is why the X-rays stop at the surface layer. For example, gold plating and many colour pigments are not as permeable to radiation as a bare wood surface. Common medieval pigments that stand out well in X-ray images include, for example, white lead and vermillion (orange-red), which contains mercury.

The light circles that stand out on the edge of Mary’s cloak and also in the chest area are decorative themes. They were created by making raised shapes out of the priming mass. The larger rings on the top edge of cloak are also remains of decoration. Larger ornaments, similar to jewels, were probably attached to these points. A wide variety of techniques were used for finishing sculptures, striving to create three-dimensional shapes and a sense of luxury on the paint and metal surfaces.

Digital collection

Archangel Michael

This statue has a large number of wooden parts of different thicknesses attached to each other. The thin wings and sword are more permeable to X-ray radiation, which is why they can barely be discerned from the background. The thicker parts appear lighter.

The sculpture also contains different wood species. Michael’s body, head and most of the dragon under him were carved from the same piece of oak. The arms and dragon’s head are made of hardwood. The change in the wood species is easily discernible in the X-ray: the hardwood parts look “softer” in terms of structure – the wood grains are less obvious. The backboard and its nail fastenings were added later to keep the statue together.

Digital collection

Saint Birgitta

The light spots in the corners of Birgitta’s eyes are paint marks that you cannot see at all when you look at the statue. There is also some paint on the book, but otherwise the statue is very bare. The painted surfaces of sculptures have often been worn down as a result of natural ageing, but sometimes they have also been intentionally stripped of paint and priming over the centuries. The latter may be the case where Birgitta is concerned. People may have regarded a worn paint surface as unpleasant, and at certain times, it has been desirable to highlight a wooden surface. In the 19th century and even in the early 20th century, sculptures were washed with lye, for example, to create an even wooden surface. This strongly contradicts the original, multicoloured appearance of the sculptures.

The surface of the statue of Birgitta has at some point been treated with wax, which also accentuates the wood surface and darkens the tone of the wood.

Digital collection

Eric the Holy

Plenty of gold and silver plated surface has been preserved on the statue of Eric. Thin leaf metal is visible in the image as light areas impermeable to X-rays. The area of the face is also light, which is due to the white lead in the colour of the skin. However, the face is not smooth like the metal surface; the paint marks can be clearly seen in the image.

Metal surfaces that sparkled and reflected light in their original appearance were an important part of medieval sculpture. Here, they depict not only the metal armour, but also the dignity and holiness of the character. The alternation of gold and silver is intentional, although silver is often darkened and can, therefore, be difficult to detect. In the statue of Eric, silver is found in the area of the neck and chest protectors, for example.

Digital collection

Saint Margaret

The metal pin in Margaret’s head was probably intended to cover up signs of the work which, however, did not produce a cavity similar to that in many other statues. There is a very distinctive crack next to it, but not exactly at the pin. The statue was made of a single piece and its back was not carved. Instead, a rather narrow cavity was made from the bottom to lighten the statue.

Margaret is trampling over the devil, who is disguised as a dragon and, according to legend, failed to kill her. The painted inside of the dragon’s mouth is clearly visible in the X-ray. According to material studies, the red pigment contains at least vermillion, and there is also white lead and possibly lead-containing red.

The nails and rectangular strips seen under the base are not part of the original assembly.

Digital collection

Job

The suffering of the sculpted Job is highlighted by the abscesses that cover his skin. The abscesses were sculpted from separate pieces of wood, which were then glued to the statue, primed and painted. The sculptor knew the subject: the tones of bloodshot and festering skin and the ragged surface of the abscess have been carefully reproduced. Originally, there were more abscesses. The dark circular marks in the X-ray indicate areas where glued abscesses have come off. In addition, there probably used to be abscesses in the areas where the paint has disappeared altogether.

The nails at the bottom hold a broken part of the leg, and there are also two wedge-like pieces of wood next to the feet.