Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

Artefact of the month – December 2019

The National Museum of Finland is showing an exhibition on Central and South American pre-historic indigenous cultures, The World That Wasn’t There, until March 2020. The artefacts are on loan from Italy. The museum’s own ethnographic collections also include a few archaeological artefacts from abroad, such as this Peruvian clay vessel.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, many archaeological discoveries in former Spanish colonies in Latin America ended up in European art markets and museums, sometimes even with the knowledge or involvement of local governments. The items came from both official excavations and looting. Once the countries finally began to value their pre-Columbian cultural heritage in the early 20th century, its export was prohibited. However, UNESCO did not ban the illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property until its 1970 Convention, and the illicit trade and export continued even after that due to loopholes in the convention. Supplementary acts, degrees and instructions have since been enacted up until the recent years, because every country has its own laws.

Therefore, acquiring this clay vessel for the museum would not be in line with the Code of Ethics for Museums of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) or our own current collections policy, because the circumstances of its original acquisition/discovery are unknown. Curt Segerstråle, who bought the vessel in Peru, sold it onward in 1932 to the Antell delegation, which managed the foundation that was used to increase the National Museum’s collections. The vessel is a part of a set of 13 artefacts, the first seven numbers of which are catalogued to represent ancient Peruvian Chimbote ceramics, but the rest are reproductions of old items. Curt Segerstråle (1895–1955) was one of the eight children of artist and author Hanna Frosterus-Segerstråle and the younger brother of artist Lennart Segerstråle. Curt Segerstråle gained a licentiate degree in philosophy and was a fishery biologist by profession. As a good country for fishing, Peru surely interested Segerstråle, although we do not know whether he was there on business. In either case, Chimbote on the northwest coast of Peru was already a fishing village in the 1930s thanks to its good natural harbour, and it later grew to its current size due to the fish processing industry.

This clay vessel in the shape of a man represents the Moche culture, Chimbote being one of its sites. The Moche people lived on the coast of the Pacific Ocean in the river valleys of Peru’s northern coast between 100 BCE and 800 CE. The vessel dates back to the Middle Moche period, circa 300–600 CE, which is considered as the heyday of the Moche culture. The hierarchical culture ruled by the priestly elite is known for its adobe brick pyramids, such as the Pyramid of the Sun in Cerro Blanco, and for elaborate moulded ceramic vessels that depict a wider range of subjects than other ancient cultures in Peru. Both sculpted and painted ceramics often depicted mythological events, which is why ceramics in particular have shed light on the ideological and religious background of the Moche culture, which placed great significance on ritual sacrifice. Portrait vessels and other clay vessels were often intended as sacrificial vessels for graves and made in hundreds at a time. Some of the ceramics purchased from Segerstråle are this type of artefacts intended for graves; they are of a much rougher make, unfinished and matt-surfaced.

This lifelike polished jar/bottle is a stirrup-spouted vessel, which was a very popular vessel shape. It was developed in the first millennium before the Common Era within the sphere of the partly contemporary Cupisnique and Chavín cultures and subsequently became dominant in all the cultures on the northern coast of Peru. The man’s face on the vessel is depicted realistically, his membership in the elite indicated by his tubular earrings and banded headdress tied at the front. The faces depicted in vessels of the Moche culture are typically represented with detail and attention to anatomy and facial features, achieving a natural effect. The figure wears a painted garment where even the knot has been painted. White and shades of red and brown were typical colours. The vessel may have been an article of daily use owned by the elite or used for storing and drinking chicha, the corn drink used for religious ceremonies.

The Moche culture waned and disappeared by the mid-8th century CE. The theories of the cause of its demise include drought caused by climate change and hostilities from the Wari culture, which spread out along the coastline. The Wari were able to utilise limited water supplies, for example through terrace agriculture, and although short-lived, only a couple hundred years, that culture is assumed to have laid grounds of the Inka state.

Heli Lahdentausta

Sources:

Ilmonen Anneli & Jyrki K. Talvitie (eds.) 2001. Kultakruunu ja höyhenviitta: Inkat ja heidän edeltäjänsä - Perun kolme vuosituhatta. Tampereen taidemuseon julkaisuja 94. Tampere.

Korpisaari Antti, Tapani Pennanen & Anneli Ilmonen (eds.) 2001. Inkat ja heidän edeltäjänsä: Perun kolme vuosituhatta. Näyttelyluettelo. Tampereen taidemuseon julkaisuja 95. Tampere.

Interview: Antti Korpisaari, 15.10.2019.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

Stirrup-spouted vessel from Peru

-

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

Trans pride bow – a carnival accessory and statement for human rights

-

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

Retro upholstered baroque armchair

-

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

Comb pendant from the St Nikolai shipwreck

-

Wooden toy horse

Wooden toy horse

-

Ashtray

Ashtray

-

Marsh horseshoes

Marsh horseshoes

-

Student Union flag

Student Union flag

-

Stylish at work

Stylish at work

-

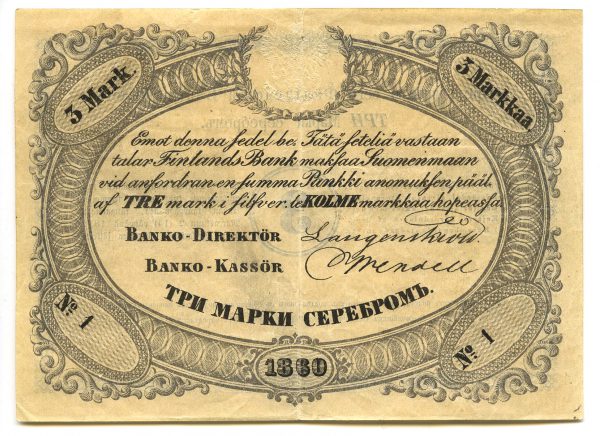

The first Finnish markka ever issued

The first Finnish markka ever issued

-

Seer's amulet

Seer's amulet

-

Photopicture from Egypt

Photopicture from Egypt

-

-

2018