Chilkat blanket

Artefact of the month - November 2020

The National Museum of Finland returned ancestral and grave item material of ancient Puebloans for re-burial to Mesa Verde in the United States in September. The museum holds also other unique items from the indigenous peoples of North America.

According to the old Russian catalogue, a textile listed with number 44 is ”a nakidki coat of the Kolosh in Sitka”. Kolosh is the name the Russians called the Tlingit living in Alaska and British Columbia on the Canadian side on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. The Tlingit consisted of 16 independent tribes, one of which was the Chilkat, living in four villages to the north of the Lynn Canal in the Chilkat River area. It was estimated that in 1880 there were fewer than 1,000 Chilkat people. The first to make so-called Chilkat blankets were probably the Tsimshians, a neighbour people of the Tlingit, but the Chilkat women specialised in weaving them in the 19th century.

The warp of the Chilkat blanket was made of Nootka cypress (Cupressus nootkatensis) bark covered with a thin layer of wool. The weft was also made from wool yarn, which was made with wool shorn from wild Rocky mountain goats (Aplocerus montanus). Some of the yarn was left undyed white, some was dyed black with spruce bark, some yellow with Evernia vulpina moss and some blueish green with copper oxide. The turquoise blue would, however, turn greenish in the goat wool. In this blanket from the early 19th century the colour has turned a dark olive green. This means that colour can be used to date the blankets; blue or bluish green indicates more recent times, when blue yarn was available from Europeans and Americans, and fabric received from them was even taken apart to acquire blue yarn.

The textile was woven in a simple frame with tall stakes rising from a base, and a wide crossbeam, from which the warp hung. The edges of the blanket are steep twill. The pattern, consisting of several sections of different colours, was made by looping, and the sections were either overlapped with each other or attached horizontally. This was achieved by twisting the weft yarn around thread made from caribou or whale sinews at the edge of each section. The weaver would copy the pattern from a template, which had only about half of the ornamental area painted on it, because the halves are identical. The men would paint the pattern on the template board in the actual size. One blanket would require the wool from three goats, the weaving would take approximately six months and the preparation for the material the same. This means that a skilled weaver could make one blanket a year. The skill was passed down from mother to daughter.

The animistic worldview of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast was also evident in the art, which focused on totem animals. An animal symbol or theme is configurative if the animal depicted is illustrated in lifelike profile, somewhat completely. When an animal is divided into parts and rearranged on the given surface, the pattern is expansive, but it too contains the essential body parts and anatomical proportions. If the entire animal is difficult to identify due to complete mutilation, the pattern is distributive. Representational themes are usually spread across the entire surface. Key themes, such as sections of specific animals, are emphasised and empty areas are filled with symbols that may carry completely different meanings elsewhere in the pattern. The manner of filling empty space is not purely decorative, it has meaning.

The pattern of the blanket usually forms a clear centre and narrow edge panels, and this is true for this blanket, as well. Exceptionally, the central pattern does not contain a face, which is depicted in small size on the top edge instead. The animal body is depicted with the help of the mouth, eye patterns to mark joints and paws signifying all of the sections of the legs. The animal is depicted as sitting frontally, and the paws would suggest that the animal is a bear or wolf. The patterns filling the side panels are wings. Pattern analysis talks of flicker wing patterns, but here the wings refer to the raven, which is a Tlingit totem animal. The animal in the main picture is depicted in profile in the side panels.

The most prestigious women and men were allowed to wear the blanket during celebrations and ceremonies, especially potlatches. Potlach means giving, and during the celebrations, affluence and authority were demonstrated and gained by donating property to guests with the intention of having it be returned with interest in the following meeting. The complex potlatch celebrations intertwined with social standing were held in connection with important events in the community, such as weddings or initiations.

The Chilkat blanket symbolises the welfare and position of a person and their family: due to the labour-intensive and long manufacturing process, only the wealthiest people could afford them. An owner might gift a blanket to another dignitary, but people of lower rank were only given pieces cut from the blanket. The blanket was used especially when dancing, and the totemistic emblem of the clan was placed on the back in the centre of the blanket, where it would move the least and be most visible. Due to their use, the blankets have been called dancing blankets, which is why they have long fringes. In addition to the blanket, festive attire would also include a similarly woven and patterned loincloth and gaiters, but the National Museum of Finland collection does not include these. The only other Chilkat blanket in the collection is newer, but dating also to the 19th ct. When a chief died, he would be dressed in the celebratory outfit and placed on display surrounded by his property for the wake. When a dignitary was buried, the Chilkat blanket was sometimes placed on the end of the wall of the above-ground tomb.

The blanket is part of a donation by Arvid Adolf Etholén (1798–1876), who served the Russian-American Company. The donation was sent in three instalments to the Coin, Medals and Art Cabinet of the Imperial Alexander University in the 1830s and 1840s. Etholén travelled Alaska, the Aleutian Islands and the coast of Northeastern Asia to map and research the areas – and collected ethnographica on his trips. His long official career culminated in a term as the governor-general of Russian America 1840–45. At that time, he would have an annual feast exchanging gifts with indigenous chiefs, meaning that this Chilkat blanket may be a present from a prestigious Tlingit.

The blanket is not on display in the museum, but it can be seen in the database Finna.

Heli Lahdentausta

Sources:

Boas Franz 1955. Primitive Art. New York, Dover Publications, Inc.

Emmons George T. 1907. The Chilkat Blanket. New York, NY, Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 3.

Holm Bill 1976. Northwest Coast Indian Art: an Analysis of Form. Seattle, Wash., University of Washington Press.

Krause Aurel & Erna Gunther 1956. The Tlingit Indians. Results of a Trip to the Northwest Coast of America and the Bering Straits. Monograph of the American Ethnological society, 26. Seattle, Wash., University of Washington Press.

Samuel Cheryl 1982. The Chilkat Dancing Blanket. Norman, OK, University of Oklahoma Press.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

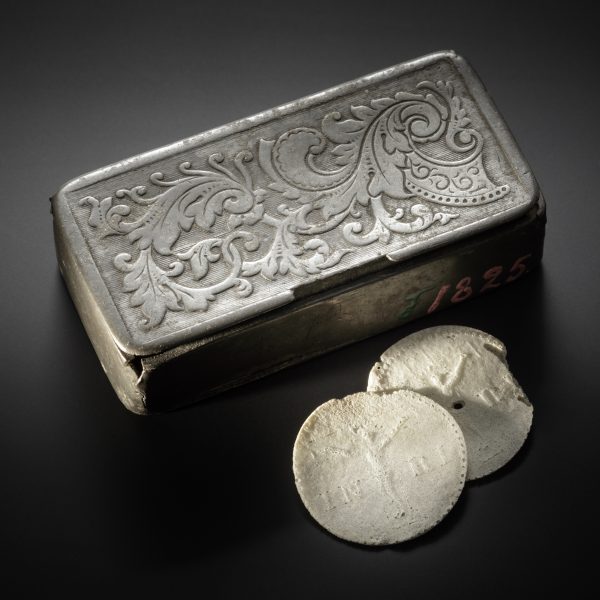

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

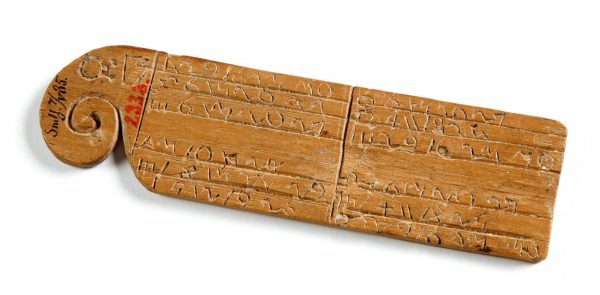

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018