A box of sacramental bread

Artefact of the month - October 2020

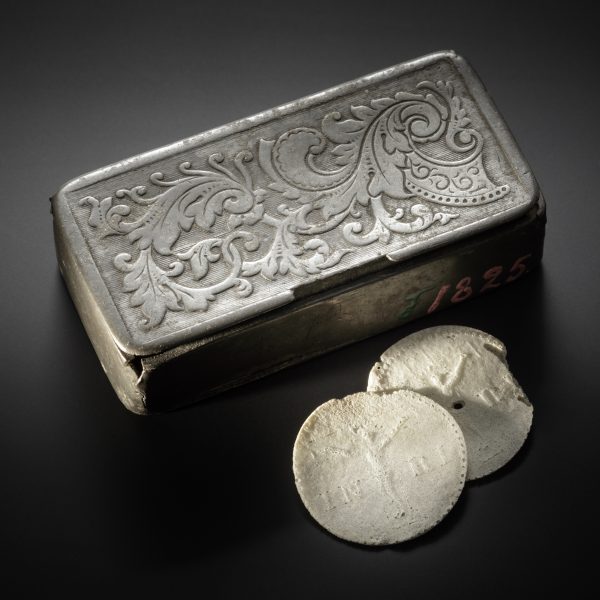

In October 1910, a tin snuff box was acquired from Särkijoki, Korpilahti for the collections of the State Historical Museum (which became the National Museum of Finland in 1917). The box, which at that time was expected to be at least 50 years old, contains sacramental bread. The item is one of those collected by J. W. Kotikoski from his home region in 1890–1910. According to the information recorded, sacramental bread had been used for many different purposes: as medicine, to improve the poor functioning of a gun and as a heart of “para”.

Sacramental bread has a long international history as a particularly powerful magical object. As early as at the turn of the 4th and 5th century, the Bishop of Constantinople is known to have decreed that sacramental bread should be mixed with wine and distributed with a spoon in order to prevent its magical use, which was widespread among the people.

For Finns, too, sacramental bread has been not only sacred but also a powerful magical object. According to folk belief, the church, its objects and sacred services contained strong otherworldly powers. The sphere of influence of these powers was sought in many different ways. The doctrine of the church was seamlessly mixed with folk religion, and the same otherworldly powers were believed to be included in sacramental bread. As a result, people smuggled sacramental bread from the Holy Communion for use in magic. Sacramental bread had many magical uses among the people, most of which were related to the pursuit of happiness and, thereby, the safeguarding of livelihoods.

One of the most essential uses of sacramental bread was the making of para. This pan-European tradition was transferred to Finland via Scandinavia. The Finnish term para is derived from the Swedish word ‘bära’ – to carry. Para was a creature made of mundane materials found at home and brought to life by magical means, often appearing in the form of a cat in the Finnish tradition. The making of para was strongly related to livestock farming and the makers were farmer’s wives, who were responsible for the livestock. Para served as an aid to its owner, helping accumulate the owner’s wealth. It was believed to steal milk from the neighbour’s cows and bring butter, grain, money or other stolen property to its owner. The belief was motivated by the idea that the amount of good fortune in the world was constant, but its distribution could be influenced by magic.

Para was made of rags, spindles or other practical materials as well as a stolen object and sacramental bread. The most suitable time for the task was the night of a feast day or a Thursday night. Thursday was considered the most powerful day of the week in folk religion even in Christian times. This was based on the old Scandinavian tradition according to which Thursday was the day of Thor, the God of Thunder, and therefore the most suitable for all kinds of powerful acts, spells and healing.

Kristian Erik Lencqvist described the creation of para in 1782 as follows:

"The head is formed out of a child’s cap by filling it with miscellaneous rags and hiding in it sacramental bread that ladies have taken in their mouths in the Holy Communion; this is how they believe they can give life to para. The belly is made out of a woman’s linen headdress and is crammed with tow. Three spindles going in different directions are attached as the legs. After that, you carry the fine creation to a church porch early one Sunday morning and keep it there for some time, and then you walk around the church nine times, all the time muttering: be born, para! A little later, it will come to life and start jumping on three legs."

Lencqvist’s description fails to mention one belief that was central to the manufacture of para: it was brought to life by drops of its maker’s blood, and at the same time it received part of its maker’s soul. Therefore, it was believed that the fate of para was tied to the person who made it: if para was caught appearing in the form of a cat and killed, the neighbour’s wife might also die. The price of making para was therefore high, and the task was not to be taken lightly.

The artefact is not currently displayed.

Raila Kataja

Sources:

Lencqvist, Kristian Eerikinpoika 2011. Vanhojen suomalaisten tietoperäisestä

ja käytännöllisestä taikauskosta. Helsinki, Salakirjat. Original:

Henrik Gabriel Porthanin tutkimuksia. Translated: Edvard Rein. SKS 1904 (1782).

Pulkkinen, Risto 2014. Suomalainen kansanusko. Samaaneista saunatonttuihin. Helsinki, Gaudeamus.

Pulkkinen, Risto & Stina Lindfors 2016. Suomalaisen kansanuskon sanakirja. Helsinki, Gaudeamus.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

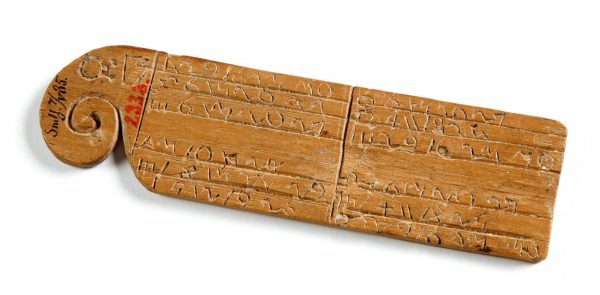

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018