Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Artefact of the month - June 2020

In the 19th century, the typical Finnish diet was meagre, based on Finnish grains: rye, barley and oats. Food management was dependent on the preservation and storage of food. Food was dried, soured, salted and smoked for winter. Sometimes there simply wasn’t enough food, and many Finns were used to going hungry in the spring and early summer. At the start of the 19th century, over half the population still had to regularly resort to eating substitute foods, such as bark.

The hunger that people felt in the spring and summer was recorded in several Finnish proverbs: Laskiainen lapset tappaa, pääsiäinen päähän nappaa, helluntai hengen ottaa, juhannus juhlan tuopi ('Shrovetide kills the kids, Easter makes you angry, Whitsun takes your life, Midsummer brings the festivities’), Kesä keikkuen tuleepi, suvi suuta vääristellen ('Summer arrives on shaky legs, twisting its face’) and Kesä kerkeimmillään, nälkä närkeimmillään (‘Summer at its highest, hunger at its worst') all tell bitter tales of the shortage of food.

However, spring and summer also alleviated hunger and expanded people’s diets. The first additional ingredients to become available in the spring and summer were milk and eggs. Cows were put out to pasture and started producing milk, which could be used to make curdled milk, sour milk, butter and cheeses. Meanwhile, eggs were collected from bird nests or self-made bird houses intended for egg-laying, called uuttu. In the early summer, diets were also expanded with sap, angelica, nettles and other plants. The most important thing, however, was to start the new crop year by tilling and sowing the fields, so that stocks could be replenished for the next winter, at least enough to keep hunger at bay for another year.

The Finnish name for June, kesäkuu, comes from the word kesanto, meaning fallow. One of the most important tasks to be carried out in June was the tilling of the fallows. Oats, barley, peas and beans were usually sown by the end of May (Urpo’s day on 25 May). Left for June were the sowing of turnips and hemp (Esko’s day on 12 June) and the planting of potatoes (Kustaa’s day on 6 June, in some regions also the day on which barley was sown).

Up until the early 20th century, sowing was carried out entirely by hand, as mechanical seeders did not start to proliferate until 1920s–1930s. Sowing was the responsibility of men and was usually carried out by the man of the house. One exception to this was Northern Ostrobothnia, where sowing was carried out by women.

A tilled field was sown by walking in a straight line. The seeds to be sown were carried in a sowing container or bag, from which the sower scattered them to the field with one hand or alternating both hands. The sowing width was marked with a club-like wooden stick, called a sitkain, or by drawing lines in the earth or leaving marking sticks. The sitkain user walked behind the sower. The marking of areas that had already been sown prevented the same areas from being sown twice. Seeds were precious – there were none to waste, so sowing had to be precise. A good sower could spread seeds to an area of 6–8 hectares over the course of an eight-hour day.

Sowing required a container. The Object of the Month is a seedlip, kylvövakka, a type of basket used for sowing, which is part of the Seurasaari Open-Air Museum’s collection. The side of the vakka, or keri, is made of bent aspen board, while the bottom board is made of pine. The ear, or grip, of the vakka is bound to the side by pine root and leather. The opposite outer side features a spruce noukka, or hook, which was used to attach the vakka to a belt or an over-the-shoulder sling while sowing. This particular object is from the Niemelä tenant farm in Konginkangas, which was the first building to be moved to the Seurasaari Open-Air Museum in 1909. The seedlip used to belong to Heikki Heikinpoika Turpeinen (born in 1827), so it was used for sowing in the 19th century.

Similar sowing containers bent out of aspen board were used in Western Finland in particular, where they were exclusively intended for sowing. A vakka had a typical volume of approximately 20 litres. A kylvövakka was usually oval in shape, making it easier to hold against one’s body. In Central Ostrobothnia, sowing containers were sometimes round and had handles. In Eastern Finland, sowing containers called kylvinkopsa were woven out of birch bark and could also be used to store flour, grains and salt. In Central Ostrobothnia, Kainuu and Peräpohjola, people also used handled baskets woven out of pine roots. In some places in Finland, people also used special sowing dresses instead of a sowing container. Made of rough tow cloth, they were garments similar to an apron or white nightdress, sometimes missing a right-hand side sleeve for practical purposes, which were only used for sowing. Sowing was sometimes followed by a celebration, during which people ate sowing bread baked back at Christmas and drank spirits, coffee or beer. These celebrations were accompanied by wishes for a good harvest that would allow people to survive until the next summer without hunger.

The seedlip is on display at the Seurasaari Open-Air Museum, in the Niemelä tenant farm’s Heikki storehouse.

Leena Furu-Kallio

Literature:

Forsgård Nils Erik, Rainer Knapas & Laura Kolbe 2002. Suomen kulttuurihistoria: Osa 2, Tunne ja tieto. Helsinki, Tammi.

Hintikka Onerva & Kirsti Häppölä 2006. Tuntematon emäntä: Kotirintama kertoo. Maahenki.

Vilkuna Kustaa & Erkki Tanttu 2007. Vuotuinen ajantieto: Vanhoista merkkipäivistä sekä kansanomaisesta talous- ja sääkalenterista enteineen, p. 24. Helsinki, Otava.

Vuorela Toivo 1975. Suomalainen kansankulttuuri. Porvoo, WSOY.

See more images and objects related to sowing on Finna.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

2020

-

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

Maternity package for undocumented migrants

-

Chilkat blanket

Chilkat blanket

-

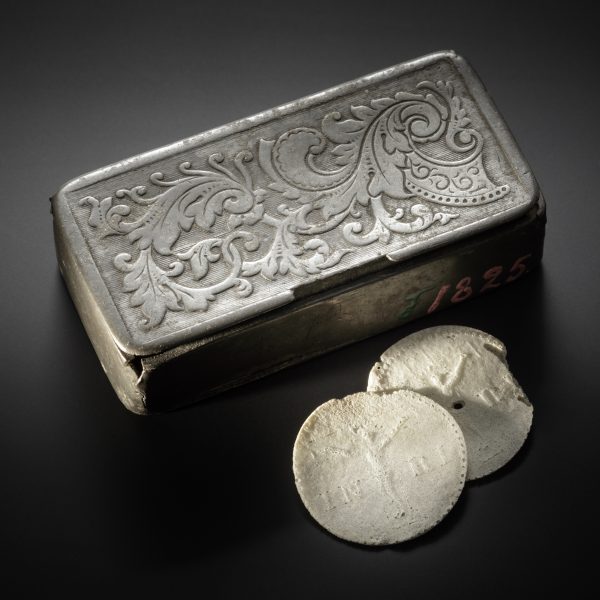

A box of sacramental bread

A box of sacramental bread

-

Tar steamer model

Tar steamer model

-

A holy family from the court of Prague?

A holy family from the court of Prague?

-

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

Mosquito hood from East Karelia

-

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

Seedlip (kylvövakka)

-

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

A box of ‘citizens’ pastries’

-

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

Oak night-box (nattlåda)

-

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

Silver coin hoard from Vieki

-

Two mermaids

Two mermaids

-

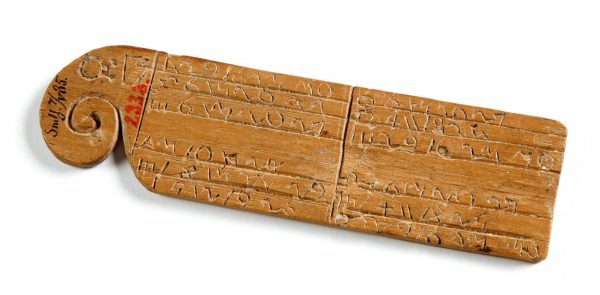

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

Carl Harlund’s wooden calendar

-

-

2019

-

2018