The mighty snake

Artefact of the month - September 2021

In the peasants’ annual cycle, September was considered as heralding the autumn. It also marked a milestone in many forms of agricultural work: people working in the fields returned to the farmyard, the livestock was brought from the pastures to the cowshed, the harvest was completed, and the womenfolk started the winter crafts. The coolness of the autumn also caused changes in the surrounding nature. After Syys-Matti (21 September), snakes were considered to have retreated to their winter places and there was no longer any need to be afraid of them.

The attitude towards snakes in the peasant society was twofold: on the one hand, the snake was seen as a fearsome threat, which was only spoken of in euphemisms; on the other hand, the snake acted as a guardian of the home, securing the success of the house. According to folklore, the snake had otherworldly powers, so the snake and its parts were believed to act as powerful medicinal substances: the snake’s spine helped with stinging and colds, its fat relieved aches and pain, its skin healed shingles and abscesses, and its teeth and the bones of its head were suitable as different kinds of magical charms. If you wanted to use snakes for medicine during the coming winter, according to an old myth, you had to catch them in September, during the week of Syys-Matti.

The snake has also been associated with many other kinds of popular beliefs: The power of the snake was believed to improve the efficiency of traps and weapons and protect a child lying in a cradle from the neighbour’s evil eye. If you killed a snake with a frog or a bird in its mouth and managed to separate them, you were endowed with the power of a healer. If you snatched a stalk of grass from the mouth of a swimming snake, this guaranteed a sure victory if you were taken to court. It was also believed that a snake could be used to do damage by summoning a bear to attack a neighbour’s livestock. The snake was also used for reading omens: its appearance in the yard meant death, and seeing it in a dream was also a bad omen. Snakes were also believed to guard buried treasures and act as familiar spirits for seers.

The storytelling traditions of Eastern Finland and Karelia in particular feature the practice of keeping pet snakes, which probably came to us from the Baltic countries. This tradition is particularly linked to dairy farming, livestock welfare and productivity. The role of the fed snake was also related to securing the house’s success and good crop. Pet snakes were fed with freshly drawn cow’s milk. If a pet snake was killed, it was believed that this would lead to the loss of good fortune with livestock and the death of the best cow on the farm. Stone formations, old sauna buildings and bases of house ovens have often been mentioned as dwelling places of pet snakes. According to popular belief, these were places of contact with the other world.

When large numbers of snakes were seen in the spring, they were believed to be holding court sessions. At that time, it was thought that they were settling their differences and planning their abodes for the summer. At the court sessions, the snakes settled in a circle with their heads towards the centre. A smooth, roundish stone, slightly smaller than an egg (“snakes’ court stone”) was in the middle of the circle. It was passed around the circle from snake to snake. Every snake had to bite a mark on it with its teeth. The crown-headed king of the snakes supervised the proceedings. It was believed that if you happened to encounter the snakes’ court session and managed to get hold of the court stone, you knew that you had an effective magic tool. It would serve as protection in dangerous ventures and protect wedding and funeral processions. The story of the golden crown of the king snake probably originates from the yellow, distinctive spots on the neck of grass snakes.

The belief that killing a snake is the responsibility of a Christian stems from the Bible’s story of the Fall of Man. With the advent of Christianity, the snake was considered the devil’s creation and the most deceitful of all animals on earth. There were many beliefs related to killing a snake: “If you killed a snake, you were forgiven nine sins, but if you didn’t kill it, you were given nine more sins.” Everyone had to kill at least one snake in their lifetime, “otherwise God would make you kill a snake with your little finger in heaven.”

Today, both the grass snake and the smooth snake are protected in Finland. The adder is the only wild reptile in Finland that has not been protected so far. Its population is declining sharply.

Raila Kataja

Sources:

Huvinen Juha 2014. Kodinhaltija, noidan liittolainen ja Tuonelan musta peto. Elätti- ja haltijakäärmetarinat ikkunana suomalaiseen käärmeperinteeseen. Turun yliopisto, uskontotiede. talonpoikaiskulttuurisäätiö.fi/images/j-huvinen-gradu.pdf (viitattu 11.8.2021)

Pulkkinen Risto 2014. Suomalainen kansanusko. Samaaneista saunatonttuihin. Helsinki, Gaudeamus.

Pulkkinen Risto & Stina Lindfors 2016. Suomalaisen kansanuskon sanakirja. Helsinki, Gaudeamus.

Vilkuna Kustaa 2002 (1950). Vuotuinen ajantieto. Vanhoista merkkipäivistä sekä kansanomaisesta talous- ja sääkalenterista enteineen. Helsinki, Otava.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

2021

-

Skittle set made of bone

Skittle set made of bone

-

Equipment of ornithologist Pentti Linkola – binoculars and a notebook

Equipment of ornithologist Pentti Linkola – binoculars and a notebook

-

Scale model of the S/S Arcturus

Scale model of the S/S Arcturus

-

The mighty snake

The mighty snake

-

Child’s national costume – for free Estonia

Child’s national costume – for free Estonia

-

A tattoo machine

A tattoo machine

-

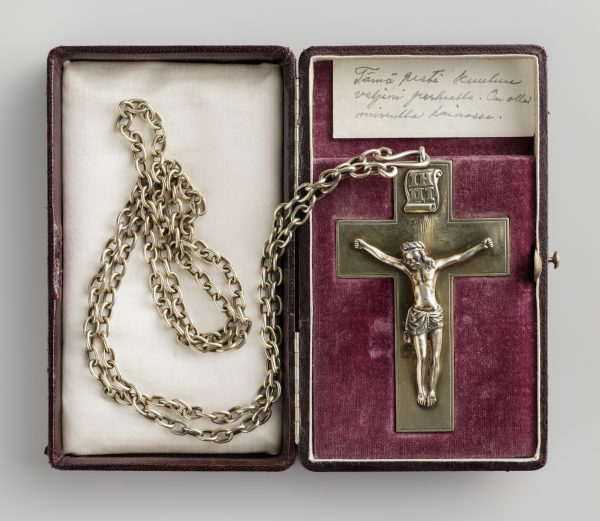

Juho Saarinen’s pectoral cross

Juho Saarinen’s pectoral cross

-

Coronation bowls

Coronation bowls

-

A hundred years ago – flapper fashion in the 1920s

A hundred years ago – flapper fashion in the 1920s

-

A table from The Friends of the National Museum of Finland

A table from The Friends of the National Museum of Finland

-

Sculpture of Bodhisattva

Sculpture of Bodhisattva

-

The stool of repentance from Vihanti Church

The stool of repentance from Vihanti Church

-

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018