Snuff and patches

Artefact of the month – April 2022

In the 18th century, a new way of life that is best described by its lightness and pleasant elegance originated from the French court. The feminine beauty ideal consisted of a carefully considered combination of make-up, hairstyle and dress. To maintain this frivolous style, a woman needed to have a considerable wardrobe and, above all, a myriad of different storage boxes.

Precious miniature boxes for varying uses were highly collectible already at the time, and people today are still willing to pay serious money for them. A snuff box (tabatière) was created after snuffing became fashionable among the upper classes in the late 17th century. As the name suggests, the artefact originated from France, where the gallant world of the court dictated the latest fashion. This luxurious necessity subtly communicated the social position of its user. Artists, especially goldsmiths and miniature painters, enthusiastically gave themselves to the new market: making boxes of four-colour gold, painted porcelain or enamel, turtle bone, shells, agate and other types of stone. These small portable objects of art also acted as prince’s tokens of grace to their inferiors and were also collected. Boxes were made for both men and women, but the ones intended for the latter were smaller in size. The flirtatious style of the era was reflected in the fact that the box was occasionally fitted with two covers, with the inner surface of the lower cover including an openly obscene erotic painting. Besides snuff, toiletries, medicines, patches, etc. were also stored in the boxes.

The ideal woman of the Rococo era was highly feminine. Poets would praise her as a shepherdess who rested or sojourned in a pastoral landscape. As the king’s mistresses, Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry have the honour of representing to future generations the feminine beauty ideal and frivolity of the 18th century. Achieving this ideal, which made it possible to have an adventure and escape from the toils of daily life, required patient sprucing-up, including make-up, hairstyle and dress. As the importance of make-up, powder and patches grew, a well-equipped dressing table with mirror and tiny boxes became a status symbol at home. Welcoming visitors and female friends around your dressing table was a common practice, as shown in group portraits painted by well-known artists of the time. The central figure in this play was naturally donning a white dressing cape, or peignoir. In Swedish, this group of people who would work on their look for hours on end are aptly described as make-up dolls and powder heroes (“sminkdockor och puderhjältar”).

Patches were made of black taffeta or thin leather in shapes varying from round to tiny figure arrangements. It is believed that the placement of the spots was used to communicate in a secret language, as was done with the favourite accessory of the time, the fan, but their main function was to highlight the whiteness of the skin and to mask flaws. Naturally, you also needed a box (boîte à mouches) to store your patches as well as snuff. Patch boxes were usually rectangular, sometimes oval or round, and resembled snuff boxes, although they were perhaps more flatter. Basically, any box would do, but the ones specially made for the purpose often had a hinged lid and a mirror inside. The porcelain and enamel boxes were suitable for the dressing table, while the small, elegant boxes were carried along. French golden enamel-embellished combination boxes for rouge and patches were also popular. Madame de Pompadour is reported to have used a swan-shaped enamel box. Much like snuffing, patches were popular among both women and men - albeit to a lesser extent among the latter.

Painted enamel-plated boxes were made of copper in England (Battersea, South Staffordshire) to the extent that it could be called an industry of its own that competed at low cost with German porcelain. Before copper was used, gold had also been coated with white enamel. Enamel boxes were also made in Germany (Dresden) alongside porcelain ones, but not to the same extent as in England. Once burnt, a box was decorated with paintings in the same way as with porcelain and then burned again.

The National Museum of Finland’s white-enamelled box was probably meant for snuff, but it could have also been used to store patches. Based on the motifs, it probably belonged to a lady. The hinged lid and the rim of the box are framed with a gold-plated brass trim. The couple on the outside cover and the shepherdess on the front, sitting beneath a bush, are depicted in colour and in fashionable dress. The trees, shrubs, terrain and the rose arrangement on the bottom are done in grisaille. The arbitrary style of painting, especially for the part of the landscape, and the subject selection in general turn thoughts directly to the leaf illustrations commonly found on fans. A portrait of a woman sitting in an armchair is painted on the inside cover to bring colour to the mostly white interior of the box. The portrait illustrates the dress, hairstyle and jewellery fashion of the time. However, the painter struggled with the right side of the woman’s neck: he has clearly not been fully familiar with the painting of this part. The index finger of the woman, wearing a rose in her hair, appears to point to her earring or possibly to the three patches on the corner of her right ear.

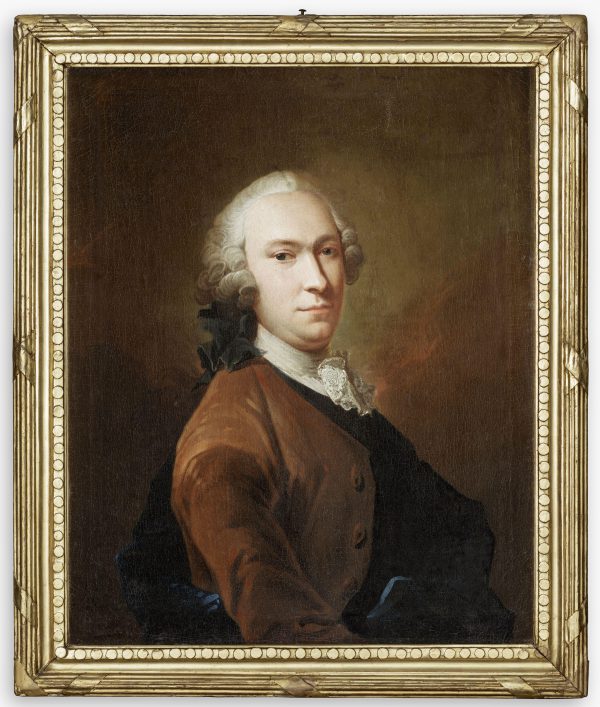

Portraits were popular decorations on the lids of fine boxes and were common even on the inner covers of enamel boxes. The skilful works of Antoine Pesne (1683-1757), who worked as a portrait painter in the Prussian court, and especially his portraits of Frederick the Great, have probably inspired the decorators of snuff boxes quite extensively. Sometimes the women in the portraits hold a fan in their hand, and naturally, they also have patches on their faces. The painted decorations on enamel boxes are of varying quality. In Sweden, women continued to wear patches in the 1790s, even though they had already become unfashionable on the Continent. As the fashion died out, snuff and patch boxes gradually disappeared from the dressing tables and continued as beautiful ornaments and collectible items.

Outi Flander

Literature

Bramsen Bo 1965. Nordiske snusdåser på europæisk baggrund. København.

Corson Richard 1972. Fashions in Makeup. Great Britain.

Lindvall-Nordin Christina 1976. Sminkdockor och puderhjältar. Kulturen 1976, s. 117—128.

Tabatière. Kulturen 1959, s. 38—41.

-

2024

-

2023

-

2022

-

Elves

Elves

-

Fire rack and gig

Fire rack and gig

-

Ndonga-language hymn book

Ndonga-language hymn book

-

President Tarja Halonen’s inaugural attire

President Tarja Halonen’s inaugural attire

-

Landscape paintings from Vyborg

Landscape paintings from Vyborg

-

Matti Haapoja – From a piece of string to a leather patch of skin

Matti Haapoja – From a piece of string to a leather patch of skin

-

Lightship Kemi’s commuter boat

Lightship Kemi’s commuter boat

-

Family rouble 1836

Family rouble 1836

-

Snuff and patches

Snuff and patches

-

A new addition to Isaac Wacklin’s oeuvre

A new addition to Isaac Wacklin’s oeuvre

-

Kataklè stool’s journey from Dahomey via Paris to Helsinki

Kataklè stool’s journey from Dahomey via Paris to Helsinki

-

The mystery of the double cloth

The mystery of the double cloth

-

-

2021

-

2020

-

2019

-

2018